For some reason, unlike science fiction, fantasy (especially high fantasy) is treated like it’s always escapist nonsense without any possibility of having substance. To most people, sword-and-sorcery fantasy will never have depth, and it most certainly will never be literary. Even when fantasy sweeps the nation (see: Game of Thrones fever), it’s because the books are enjoyable, not because they say very much about anything.

Being someone who loves sword-and-sorcery fantasy, “serious” literature, and social justice, the role of high fantasy in literature and in life is sometimes a sticky one. Yes, the majority of fantasy is escapist nonsense that, if it says anything, uses its voice to reinforce the sexist and racist norms of our society. However, that isn’t something inherent in the fantasy genre or in genre writing. You’d certainly have a case for arguing that much of literature, regardless of genre, reinforces all the bad things in inequitable societies like ours.

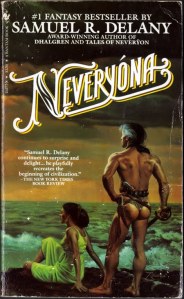

But for whatever reason, fantasy gets to bear the brunt of this injustice. Perhaps it’s because the covers of books, even ones with interesting things to say, ones you might even be tempted to call literary, often look like this:

I personally find nothing wrong with this cover, but I can understand why an ordinary person might pick this book up and think they know what they’ll find inside. Actually, they have no idea.

The plot synopsis probably doesn’t help: “For Pryn, a young girl fleeing her village on the back of a dragon, Neveryona becomes a shining symbol just out of reach. It leads her to the exotic port city of Kolhari, where she talks with the wealthy merchant Madame Keyne, walks with Gorgik the Liberator as he schemes against the Court of Eagles, and crosses the Bridge of Lost Desire in search of her destiny.” As interesting as I find it, others might read it and just think, oh just another book about dragons and destinies.

Of course, I didn’t choose this book randomly. Samuel R. Delany has a reputation for being one of the more literary-minded fantasy (and science fiction) writers, and for good reason.

Neveryona‘s chapters begin with excerpts from the likes of Susan Sontag, Julia Kristeva, Hannah Arendt, and Barbara Johnson (all women, as well as dense thinkers, which I think is important to note). If so inclined, you could very easily write a postcolonial analysis of the novel, particularly since the novel spends a lot of time deconstructing the real meanings of civilization and barbarism.

For example, Delany presents the now fairly well known idea that nature is an idea constructed by civilization. At one point, a character (Gorgik the Liberator) notes, “except some of the more primitive shore tribes along those bournes where civilization has not yet inserted its illusory separation of humans from the world which holds them.” This statement is a postcolonial goldmine. Not only does it include the civilized/barbarous dichotomy, but it clearly is nudging at the certainties civilization has invented and imposed on the world. This apparent knowledge is described as “illusory,” or deceptive. Civilization does not know everything it thinks it knows.

Pryn, the main character, is often confused about where the divisions between country, suburb, and city lie. This, for the sake of the story, is because she is new to the area. However, the subtext deals with not only the physical boundaries between the civilized and the barbarous, but also the ways in which it is difficult to tell which is which, without civilization there to explain it to you.

The novel begins with an interesting incident regarding language, one that I think is significant to consider in the context of the definition of civilization. Pryn writes her name in the dirt, but writes it “pryn,” “because she knew something of writing but not of capital letters.” It is important to note that she is a girl of the rural mountains, not of the city. It takes a woman who has traveled to “civilization” to teach her about capitalizing the first letters of names. Civilization bestows this knowledge onto barbarians, who are expected to learn civilization’s ways.

Although she is not from the city, Pryn is also not a “barbarian” as such. There are specific people who are known to be barbarians, namely the tribes to the south. Thankfully, these tribes seem to be white. (I say thankfully, because I’m tired of desert “barbarians” being represented by brown people. Of course, Delany being black himself, it would be strange for such an otherwise self-aware writer to lapse into racism.) These tribes are apparently nomadic, do “barbaric” things like weave copper wire into their ears, and talk with funny accents. I’m interested in whether or not the geographic position of the barbarians was intended to signal back to modern-day America. After all, the Northeast defines its own civility by the perceived barbarity of the Southeast. In both cases, the South is the Other by which civilization defines itself.

I’m also interested in what role sexuality plays in the novel. (Full disclosure: I haven’t actually finished the novel yet.) From what I’ve read about Delany, he has been known to write frankly about sexuality, calling some of his work or parts of his work pornography. Because it’s very clear Delany is a thoughtful writer, I would like to compare this work with the sorts of misogynistic sex scenes of other writers, and figure out what (if anything) makes Delany’s empowering or equitable. I’m also interested in looking at how Delany’s own sexuality (he’s gay) may or may not have influenced his writing of sexuality. I’m hoping that Neveryona delivers in that respect, because otherwise the Bridge of Lost Desire is a bit of a tease.

I also hope to see whether or not race plays a larger role in the deconstructing of civilization and barbarism. So far, Delany seems to be unpacking a general definition of the two loaded terms, but not approaching the racial definitions. There are plenty of people in Kolhari with undisclosed ethnicities, as well as people described as pale or darker, so it’s hard for me to tell right now if he will approach race directly or not.

I can’t imagine that the rest of the novel will disappoint me, however, because not only is the worldbuilding wonderful, but the novel features a well-drawn, dragon-riding, 15-year-old girl protagonist, and I have no gender-related complaints about the characters. Don’t be too surprised if I follow up this post with a more in-depth analysis of the novel.

For now, though, I am confident enough to say that, while Neveryona would probably be enjoyable for your average fantasy reader, it is also a rewarding experience for more academic or literary-minded people. The subtext is rich and thought-provoking, and it lends itself to various kinds of analysis, not just postcolonial. While many people may still deride swords-and-sorcery fantasy for being fluff, Delany’s work makes it clear that fantasy can be so much more than people think.

-Joanna